Last starlight for the ground-breaking Gaia mission

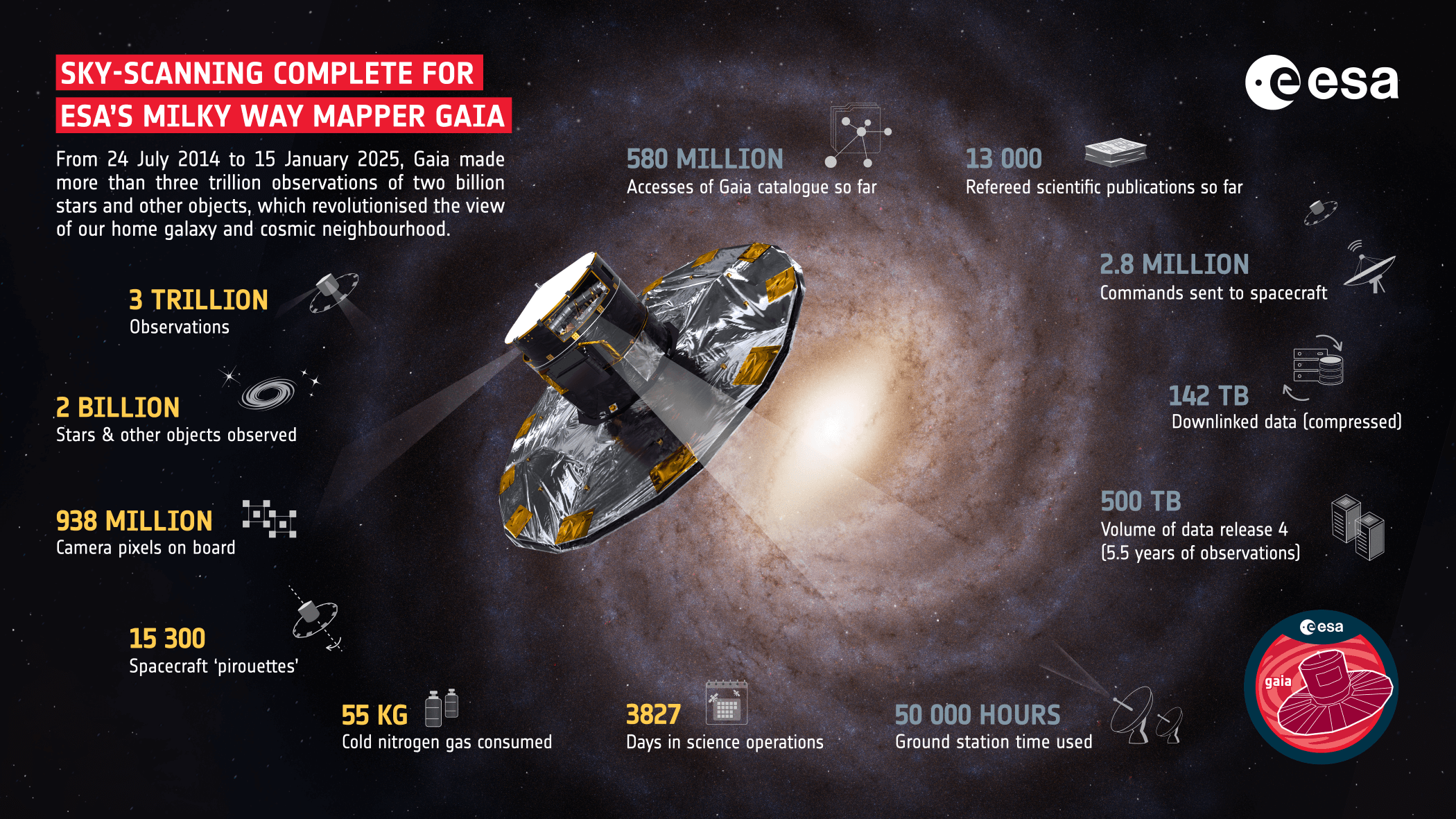

The Gaia mission, the European Space Agency (ESA) most ambitious project to study the history and structure of the Milky Way, has completed the sky-scanning phase of its mission, racking up more than three trillion observations of about two billion stars and other objects over the last decade to revolutionise the view of our home galaxy and cosmic neighbourhood. Since the beginning, the mission has involved a group of astronomers and engineers from the Institute of Space Studies of Catalonia (IEEC), and the Department of Quantum Physics and Astrophysics and the Institute of Cosmos Sciences (ICCUB) of the University of Barcelona. The team led by Jordi Portell at the ICCUB Technological Unit (ICCUB-Tech), located in the Barcelona Science Park, has played crucial role in the development of the project.

Launched on 19 December 2013, Gaia’s fuel tank is now approaching empty – it uses about a dozen grams of cold gas per day to keep it spinning with pinpoint precision. But this is far from the end of the mission. Technology tests are scheduled for the weeks ahead before Gaia is moved to its ‘retirement’ orbit, and two massive data releases are tabled for around 2026 and the end of this decade, respectively.

Gaia has been charting the positions, distances, movements, brightness changes, composition and numerous other characteristics of stars by monitoring them with its three instruments many times over the course of the mission. This has enabled Gaia to deliver on its primary goal of building the largest, most precise map of the Milky Way, showing us our home galaxy like no other mission has done before. As such, we now also have the best reconstructed view of how our galaxy might look to an outside observer. This new artist impression of the Milky Way incorporates Gaia data from a multitude of papers over the past decade.

A model image of what our home galaxy, the Milky Way, might look like edge-on, against a pitch-black backdrop, based on data from ESA’s Gaia space telescope.: ESA/Gaia/DPAC, Stefan Payne-Wardenaar. CC BY-SA 3.0 IGO.

“Today marks the end of science observations and we are celebrating this incredible mission that has exceeded all our expectations, lasting for almost twice its originally foreseen lifetime,” says ESA director of Science Carole Mundell. “The treasure trove of data collected by Gaia has given us unique insights into the origin and evolution of our Milky Way galaxy, and has also transformed astrophysics and Solar System science in ways that we are yet to fully appreciate. Gaia built on unique European excellence in astrometry and will leave a long-lasting legacy for future generations.”

Xavier Luri, professor at the Department of Quantum Physics and Astrophysics, director of the ICCUB and member of the IEEC, stands out that the Gaia team at UB and IECC worked on the mission since its beginnings, around 1997. “Since then, they have participated in all its phases, from defining the scientific case and industrial design to data processing and scientific exploitation. Now, although Gaia is ending its observations, several years of work remain to fully process all the data collected over these years and publish two additional data releases (DR4 and DR5).”

The most extensive and precise map of the Milky Way

Gaia’s repeated measurements of stellar distances, motions and characteristics are key to performing ‘galactic archeology’ on our Milky Way, revealing missing links in our galaxy’s complex history to help us learn more about our origins. From detecting ‘ghosts’ of other galaxies and multiple streams of ancient stars that merged with the Milky Way in its early history, to finding evidence for an ongoing collision with the Sagittarius dwarf galaxy today, Gaia is rewriting the Milky Way’s history and making predictions about its future.

In the process of scanning the stars in our own galaxy, Gaia has also spotted other objects, from asteroids in our Solar System backyard to galaxies and quasars – the bright and active centres of galaxies powered by supermassive black holes – outside our Milky Way.

For example, Gaia has provided pinpoint precision orbits of more than 150 000 asteroids, and has such high-quality measurements as to uncover possible moons around hundreds of them. It has also created the largest three-dimensional map of about 1.3 million quasars, with the furthest shining bright when the Universe was only 1.5 billion years old.

Gaia has also discovered a new breed of black hole, including one with a mass of nearly 33 times the mass of the Sun, hiding in the constellation Aquila, less than 2000 light-years from Earth – the first time a black hole of stellar origin this big has been spotted within the Milky Way.

Credits: ESA/Gaia/DPAC, Stefan Payne-Wardenaar. CC BY-SA 3.0 IGO.

While today marks the end of science observations, a short period of technology testing now begins. The tests have the potential to further improve the Gaia calibrations, learn more about the behaviour of certain technology after ten years in space, and even aid the design of future space missions.

After several weeks of testing, Gaia will leave its current orbit around Lagrange point 2, 1.5 million km from the Earth in the direction away from the Sun, to be put into its final heliocentric orbit, far away from Earth’s sphere of influence. The spacecraft will be passivated on 27 March 2025, to avoid any harm or interference with other spacecraft.

» Link to the news: ICCUB website [+]